May 8, 2024

EP. 153: How can we incorporate mindfulness into the classroom?

Research finds that mindfulness can help decrease stress and anxiety while strengthening resilience and emotional regulation in adults and children. This is why the use of mindfulness programs in schools is becoming more and more popular.

What exactly is mindfulness? What are its benefits for students? And how can we incorporate mindfulness into the classroom?

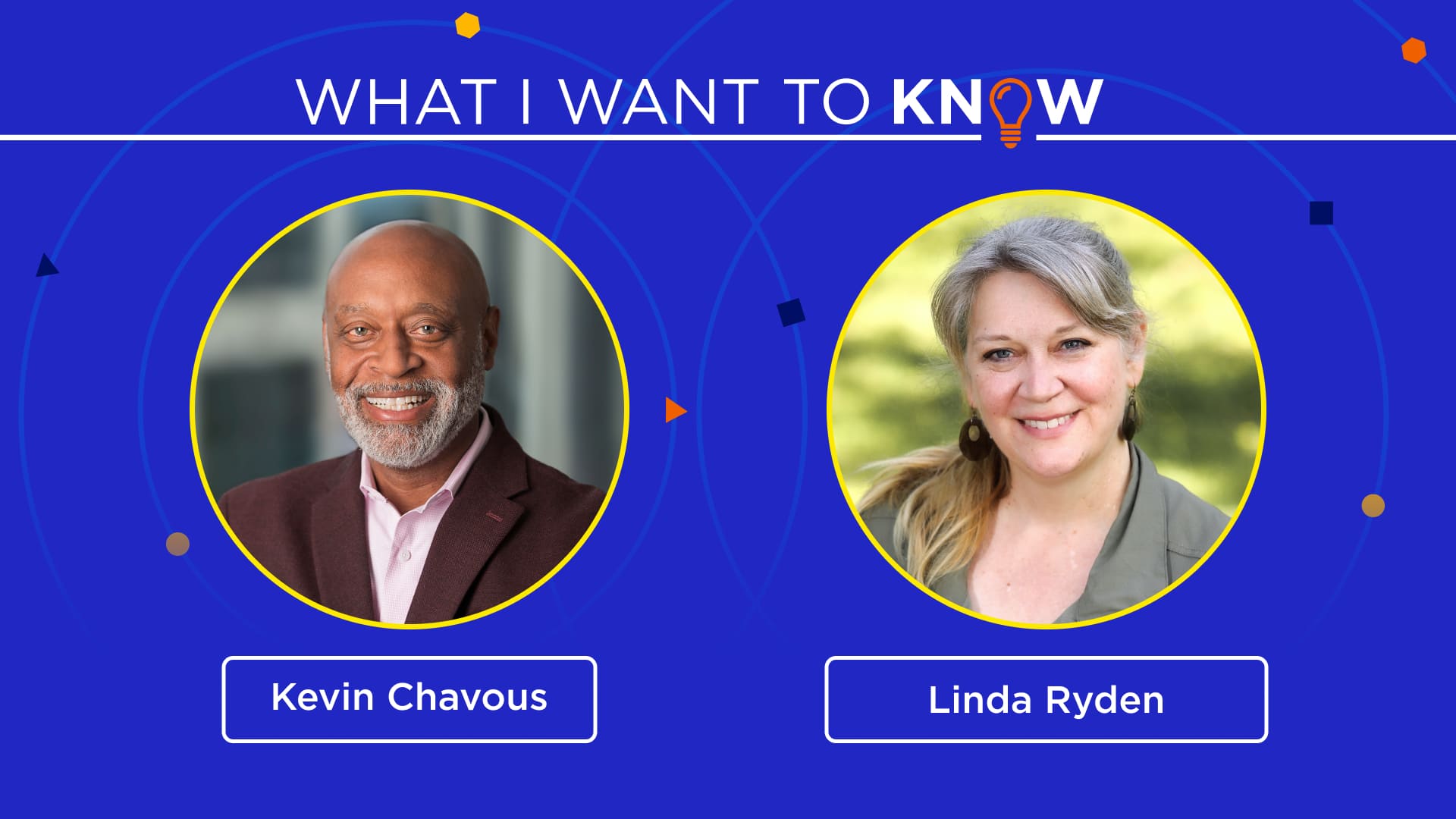

In this episode, Linda Ryden joins Kevin to share how we can incorporate mindfulness into the classroom.

Listen on: Apple Podcast, Spotify

Meet Linda

Linda Ryden founded Peace of Mind, a nonprofit organization dedicated to equipping children with mindfulness tools.

Linda is also a teacher and the author of six mindfulness-based children’s books.

Kevin: Research finds that mindfulness can help decrease stress and anxiety while strengthening resilience and emotional regulation in both adults and in children. This is why the use of mindfulness programs in schools is becoming more and more popular. What exactly is mindfulness? What are the benefits of mindfulness on students? And how can we incorporate mindfulness into the classroom? This is “What I Want to Know.” And today I’m joined by Linda Ryden to find out.

Linda Ryden is the founder of Peace of Mind, a nonprofit organization dedicated to equipping children with mindfulness tools. Linda is also a teacher and the author of six mindfulness-based children’s books. She joins us today to share how we can incorporate mindfulness into the classroom. Linda, welcome to the show.

Linda: Thank you so much for having me on. This is very exciting.

Kevin: Your work is so fascinating, and I think it’s timely. But the first question I want to ask you is, how did you get into this area of mindfulness? That is a big question, particularly with what’s going on in the world today.

Linda: This really goes back like 20 years. When my kids were in elementary school here in D.C., I was teaching at their school and I was a music teacher. And this was right like maybe 6 months after 9/11. And, you know, as you recall, it was a very scary time in D.C. It was a very scary time in the country. And it was a scary time, sort of like now, to be a parent and a teacher. And I really started to think in the aftermath. I really started to think that like we really weren’t doing anything in school to make the world a more peaceful place, where there was really no focus on any kind of community engagement. There was just, you know, a lot of academics. And I thought that there really was more that could be done to bring peacemaking into the schools.

I’m sure you remember Colman McCarthy.

Kevin: Yeah.

Linda: He was a columnist at The Post for a long time. And when he retired from The Post, American University asked him if he would teach a course in writing, and he said no. But he said, “I’d rather teach peace.” And he started these peace studies programs that he first taught at American. And then he started teaching at Wilson High School and Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School. And he was teaching kids about sort of the history of peacemaking and the people who had been trying to make the world a more peaceful place.

And so I heard him speak, and I thought, “You know, that’s what I want to do. I’d rather teach peace too.” And so I started to think about how I could translate that for younger kids.

Kevin: That’s really fascinating. It’s really fascinating because I remember that time well in D.C., as you know, and one thing you said struck a chord with me, and we’ve seen it all over the country. Because of the academic shortfalls that have existed over the last 20, 30 years, so many kids graduate from high school, even today, unable to read or write or count or even be proficient at grade level, that we spent a lot of time, and I know I did it, looking at how we could improve the academics. But now I think there’s a better understanding that that’s sort of the second step. The first step is understanding who you are, having the right sort of mental health, social environment, and understanding how to interact with other people. All those things that we call soft skills, Linda, wouldn’t you say those are really the hard, important skills?

Linda: A hundred percent. A hundred percent. I mean, that was really the evolution of this program. You know, as I was trying to think of, you know, ways to teach peace, one of the things that I started teaching was conflict resolution. And at that time at our school, there was really a lot of fighting. It was a big problem. Parents were up in arms. Teachers were up in arms. And so, you know, we thought conflict resolution skills are what the kids needed.

And so I really threw myself into teaching it. And I think I was teaching it really well. And what I found that was the kids were intellectually taking in the lessons, and in class they could role play, act out how to work out conflicts, but when they’d go out to recess, they’d all get into fights on the playground. And they weren’t using any of the skills that I had been teaching them.

And I remember a day when some kids got sent to me after recess because they were fighting, and I was supposed to help them work it out. And they were all, you know, mad. And, you know, and I was like, “Guys, why didn’t you use the conflict resolution skills we’ve been learning?” And they looked blank. They were just like, “Well, I was so mad I couldn’t think.” You know? And I was like, “Oh.” And so I thought like there’s really something missing from what I’m teaching. And I used to joke that the books that I read about conflict resolution were all like, you know, easy steps to conflict resolution. And step one was always calm down. And then there were no instructions in that part. How do you calm down?

So that’s what I really wanted to figure out. Like how could I teach the kids how to notice when they were getting mad, and then some skills to help them to calm down a little bit so that they could then work out the conflicts? That’s when I started to learn about mindfulness. And it was something that I was familiar with, but I wasn’t, you know, a practitioner. And I was pretty nervous about bringing it into school because this was a long time ago, when people weren’t doing that kind of thing back then. But I thought I would try it out.

And so I started to teach very simple breathing practices to the kids. The kids loved them. And we started to notice a really dramatic decrease of fighting on the playground. And just after like a few months, suddenly the kids were able to notice when they were getting mad, they were able to calm themselves down a little bit, and then they could use the conflict resolution skills that I was teaching them.

And it was really something. Like we used to have what we called the refocus room, and that was a place where kids would be sent during recess when they were getting into fights. After a few months, the teacher who was on duty in there, she was like, “There’s nobody in here. This shouldn’t be a duty post anymore because no kids are getting sent in here.” So it was really dramatic.

And so then I really started to wonder why that was true, like what was actually happening. And so I started to learn more about the brain science behind mindfulness. And there’s sort of the neuroscience of anger and to try to understand what happens in your mind when you get angry and what happens in your brain. And I learned, you know, a very small amount of brain science, but it was very impactful because I learned that what those kids were telling me about how they couldn’t think when they were mad was actually based in brain science.

Like, when you are angry or triggered in some way, the amygdala, the part of your brain that is there to be like a security guard and protect you, takes over your brain. And it turns off the parts of your brain that think and the parts of your brain that remember, and it just puts you into fight, flight, or freeze mode. And so it can just quickly react in ways that can be very helpful if you’re actually in danger, but can be very harmful if you’re not in danger, but you’re just angry or scared. So, you know, if you’re at recess and somebody takes the basketball away from you, you’re probably not in danger, but you might be mad. But you might react as though you’re in danger and start to fight.

So when I realized that was what was going on in our minds when we get angry, then I learned that just the act of sort of deliberately taking slow deep breaths sends a message to the amygdala that you’re not in danger. And so you can start to calm that part of your brain. The parts of your brain that think, that prefrontal cortex can kind of come back online. And then even though you still can be angry about something, you can express how you’re feeling. You can try to work out the conflict. You can advocate for yourself. Like it changes everything.

It also gives you kind of your power back. I always say to the kids, like when you’re out of control, you’re giving your power away to other people. Like people can push your buttons, people can make you do things that are not in your own best interest because you’re not thinking. And so if you can get control of your brain and your body, then you can advocate for yourself and say like, “This is what happened and this wasn’t right, and this is why I’m upset.” And people can hear you and people can listen, and, you know, maybe your needs will be met or the injustice will be seen or whatever it is that you are angry about.

Kevin: What’s fascinating is that and I really am so glad the country is more focused on this. You mentioned at the time, 20 years ago when you were talking about this, it wasn’t really fashionable. In fact, sort of the woo-hoo stuff and all that. But I remember during that time, and I think I mentioned to you, and I have to give a shout-out to Dr. Rutherford at Fletcher-Johnson Elementary School, working with Russell Simmons. And they put in meditation, and this was during the crack epidemic, and, you know, it was in Southeast D.C., and there were some real, real major drug wars going on there, and the kids were consumed by this.

That’s when I realized by just that process of understanding your breath and taking a step back and, as you said, lowering the likelihood of fight or flight or, you know, fright and all that, that you’re able to create at least the beginnings of conflict resolution because conflict resolution is almost at the backend of the process of being able to get there. And to hear you talk about it, which you did really so eloquently, I think people now are understanding that this is so, so important. And since you started that process, it’s grown, and now you’re in a lot of schools. Talk about how you socialize the school community to understanding and then potentially adopting this approach.

Linda: Yeah, it really took time. You know, as you know, like trying to change anything in schools is a difficult and long process. And I was really trying to change the school that I was teaching at, sort of from the inside, and I eventually became the full-time peace teacher. This was at Lafayette Elementary School in Ward 4. And that was . . . my peace classes, peace of mind classes became one of the specials that the kids had. So they’d go to art class or they’d go to music class, they’d go to PE, and they’d go to peace class. And so every child, from pre-K to fifth grade, was having a weekly class where they were learning about mindfulness and brain science and conflict resolution, and then how to apply those skills to social justice issues.

And so that, for a while, most of the teachers were kind of leaving that stuff to me to teach. And it wasn’t like a school-wide thing. Even though all the kids were learning this, it was a little bit harder with the adults. But I started to have classroom teachers who were realizing that if they used the mindfulness practices with their kids after recess or before a test or something, that it made a big difference. And that the teachers who had like a mindful moment every morning with their class, the behavior in their class was better, and the community in their class was better. Other teachers started to notice that and joined in. And eventually our administrators decided to mandate that everybody had to do a mindful moment every day or even two mindful moments every day. And so it started to grow.

The kids were really the best ambassadors though for this. I had a group of fifth graders who were I called mindful mentors. And they would volunteer to go and lead mindful moments in the other classrooms at the end of the day. And when I first had this idea, I thought maybe like five or six kids would show up. And the first time we had a meeting for it, 65 fifth graders showed up, and they all wanted to be mindful mentors. And so they were just, you know, spread out across the school twice a week teaching mindfulness to the kids. And when the teachers saw that, then they really started to realize that this was something bigger and that they wanted to incorporate into their own classes. So it took a while.

And then as our program started to grow, there was a story in “The Washington Post” about it, and people started to come and visit my classroom and ask me, “You know, how can I do what you’re doing?”

And I really didn’t know what to tell them. I didn’t have a curriculum written. I had, you know, tons of notebooks everywhere. But I realized that I had to write something that I could share. And so I partnered with a wonderful friend named Cheryl Dodwell, and together we wrote the first volume of the curriculum, and we started to share it with anybody who was interested. We put it on Amazon. We had, you know, made a website. And it was really popular. And so it got to the point where we founded a nonprofit organization to share the curriculum. We now have a curriculum that goes from pre-K to eighth grade, and we train teachers who are interested in using the curriculum in all over D.C. and across the country. And we’ve really done that without any advertising.

People are just really looking for things. And a lot of the social and emotional learning curricula that are available, haven’t really been tested in classrooms. Most of the time they’re not written by teachers, and they are things that adults think kids will like, but that kids don’t really like. And so what’s really different about Peace of Mind is that every single lesson I taught over and over and over again in my classroom and that there was like this little laboratory that I had. And I realized that, you know, every kind of kid that I was seeing was interested in these lessons and was learning this way. And we did pilot programs in other schools so that we could find out if the curriculum still worked, if somebody else was teaching it, and if it was in a different neighborhood and there was a different demographic, and it did work.

And so after 20 years of teaching full-time, in June, I left the classroom, and I’m now full-time working at my nonprofit, Peace of Mind. And we are spending most of our time training teachers, but also creating new resources. And dealing, you know, as you mentioned earlier, you know, since the pandemic, learning loss has become a huge issue. And a lot of schools, even though they know that social and emotional well-being of kids is so important, it’s almost like they just don’t have time to address it because they’re so busy doubling down on academics, which I think is a big mistake. But that’s what is happening.

And so we’re trying to find ways of meeting kids wherever they are. So we’re creating digital resources that kids can access on their own through YouTube. I have a podcast. I’ve written a series of storybooks, and we’ve put up free read aloud videos of them. So if a child is living somewhere that doesn’t have Peace of Mind as an option, they could still access these materials in some way, through the videos, through the podcast, through the story books.

So we’re just really trying to be flexible and fit in, in lots of different ways in schools. We have schools where they are using the model that we had at Lafayette, where you have a peace teacher who teaches all the kids. But at most schools it’s maybe a counselor or a social worker who’s teaching the curriculum. At some schools, every classroom teacher teaches the curriculum to their own class. Like Ross Elementary, down in DuPont Circle, we trained the whole school. And so every teacher there at Stokes, a public charter school, in Brooklyn, every teacher there teaches the curriculum themselves. And so it varies depending on what a school can manage and what they’re interested in. We just try to be flexible.

Kevin: And let me ask you about that, because, first of all, I think we should take a step back because for a lot of people it’s becoming more fashionable. So they hear mindfulness. A simple question, what is mindfulness? And you talked about mindful moments or mindful practice. What does that mean? Because there are a lot of parents out there who they like the way this sounds, but they may not understand exactly what it means.

Linda: Yeah, it’s interesting because mindfulness is one of those words that has a lot of different connotations. And even when kids come into my classroom for the first time, you know, they’ll kind of joke and they’ll sit, you know, cross-legged with their hands like this, and they’ll, “Om.” You know. And I’m like, “Nope. Like, that’s not at all what we’re doing here. Like, what we’re doing is completely different. You know, it’s based in science.”

But really, I mean, mindfulness is really just about paying attention. And in practice, what we’re teaching are three different things. We’re teaching kids breathing practices that they can do. And these are simple things, like take five breathing, for example, where you just trace your hand. And when you trace it up, you breathe in. And when you trace down, you breathe out. And you just take five slow deep breaths while you’re tracing your hand. That could be a mindful moment.

We do something called four square breathing where you’re sort of drawing a little square in front of you and you breathe in, and then you hold your breath, and then you breathe out, and then you wait. And these are just ways of slowing down your breath. And when you add hand movements to them, it’s more fun for kids.

And so we teach these breathing practices and explain to the kids why they’re important and how their brains work and how the breathing practices are related to the brain science, which makes it a lot more accessible for kids, especially older kids when they, you know, might be more skeptical about what, you know, this whole mindfulness thing is.

Then we have what we call metacognition practices, and that’s where you start to pay attention to what your mind is doing and you pay attention to your thoughts. I always say to the kids, “It’s just thinking about thinking,” right? And so you might sit quietly and try to count 10 of your breaths. And it sounds really easy, and it’s actually really hard because once you get to like three breaths, usually your mind starts to wander and think about something else. And so we teach the kids how to notice what their mind is doing, and then to start to learn how to get their mind to do what they want to be doing.

I wrote a book about this called “Quinn and the Worry Channel.” And the idea is that you imagine that your mind is like a little TV. Like, you have a little TV over your head and you have a remote control. And you might, you know, choose the channel. Like, “I’m going to listen to the teacher,” or “I’m going to focus on my breath.” But your mind can just pick up that remote control and change the channel to the, you know, what’s for lunch channel or the video game I’m playing channel, or whatever it is. And that’s totally normal and everybody does it.

But like if you’re a kid in school and you’re being asked to pay attention all day long, which is basically what we’re asking kids to do, and I always tell them, that’s completely unreasonable. Nobody can do that. But, you know, I’ll try to help them understand that they can notice what their mind is doing. Like, “Oh, I actually wasn’t listening to the teacher. What was my mind doing?” And when you can notice what your mind is doing, then you can redirect it. That’s very powerful and very liberating. Some of us, you know, really I was a big worrier my whole life, and I was always worried about things. And it was like my mind was stuck on this worry channel all the time.

And once I learned to realize that that was what was happening, I could change the channel to something else. You know, I could make a choice that I didn’t really want to sit there and imagine bad things happening to people that I love. You know, it’s not a fun activity, right? So I could change the channel with practice.

So we teach these breathing practices, we teach these metacognition practices, and then we teach compassion and gratitude practices. And those are really simple things like just thinking about a person and then thinking some kind thoughts for them, maybe happy, maybe healthy, maybe peaceful, and then noticing how it makes you feel. It’s like an experiment. And when you think those thoughts about different people, you might have a different feeling and reaction in your body, and that’s okay.

But there’s a lot of research showing that people who do compassion practices regularly really do start to treat people differently and treat them with more kindness. And it really just goes to show, you know, that kindness is something that can be learned and practiced. And it’s a big part of what we do in the Peace of Mind curriculum is to give kids lots of opportunities to practice kindness. You know, we can be taught to hate people. We can be taught to be kind to people. It really depends on where we’re putting our focus and our energy. And so we’re trying to teach kids the sort of radical act of kindness and love, especially for people that you don’t like. You know, it’s still possible to be kind to people even if you don’t like them. And so . . .

Kevin: You know, what’s fascinating about all this is that this whole idea of mindfulness and not just controlling your mind or your thoughts, but recognizing those thoughts. I mean, I think that many people have suffered in silence for years because they did not have the tools to understand where their mind was drifting. And the fact that, you know, like I love the remote, TV and on top of your head, the remote channel thing, I love that reference because you actually can sort of redirect it. And for children and you use your own personal example of being, you know, a chronic worrier, if you continue to go down that path, it also leads to self-destructive behavior, if you don’t hold it in check, or violence that is unleashed on others.

And one thing I wanted to ask you, because we both know how schools operate, but one of the challenges I see in incorporating this in schools, which is needed, is something you alluded to. Like, early on, you were the peace class teacher, and other teachers will say, “You know, this is too much to do. Just, you know, you do it.” And then now you have some schools that, you know, you mentioned Stokes in there, that’s a great school, that they incorporate everyone. Isn’t it a challenge when everyone is not involved because, you know, how can a teacher really maintain this idea of mindfulness or mindful thinking with students if they haven’t embraced it, or to use the right term, I guess, they’re not embodying it themselves?

Linda: It’s such a big problem, and it’s like this chicken and egg thing that we’re always trying to figure out. Because I really think that one of the benefits of teaching the Peace of Mind curriculum is that the teacher gets to learn about mindfulness and model learning it and model grappling with it and trying it out with their students. And it’s a very beautiful bonding thing to do in a classroom. But people are resistant, you know, to trying it and mostly really because of time. And, you know, sometimes I think like, you know, maybe the most important thing is to focus on the social and emotional well-being of the teachers, because if we don’t have that, then there’s no way that they can take and really attend to the social and emotional well-being of the children.

Kevin: Yeah. And I hate to cut you off, but first of all, I’m getting older, so I’ll forget what I want to say, so I have to get it out, okay, so we’re clear. But you’re absolutely right. And shouldn’t this be incorporated in teachers’ professional development across the board? Because let me give you an example. It’s hard, as you said, for anyone to pay attention for six hours a day to just one thought or one thing that’s in front of them, a teacher or what have you. It’s easy for kids’ minds to drift in particular. But teachers who haven’t received the benefit of understanding “mindfulness,” they will engage in the behavior that we all grew up with. “Johnny, you’re not paying attention. I’m going to send you to the principal’s office or place you in detention.” As opposed to having, you know, working the child through this idea of being able to control their own remote control. You see what I mean?

Linda: Yeah.

Kevin: It feels like that, while this makes sense and while kids are embracing it because they’re getting taught it at an early age, we have a lot of adults who interact with kids everyday, who need to figure out how to control their own remote control.

Linda: Absolutely. And that’s really why we focus so much on teacher training, because, you know, I mean, you can just buy our curriculum and start using it. You can. But with training, we can really address things like that and help . . . I mean, I found that learning mindfulness was very helpful for my students, but it changed my life as a teacher. I used to be the, “Johnny . . .” And when I started practicing mindfulness, I would say to the kids like, “Oh, I can feel that I’m getting angry right now. Like, I’m getting frustrated that some people aren’t listening.” And I would describe the feeling. “Like, I feel it right in here in my chest, and so I’m going to stop and I’m going to take a couple of deep breaths.” And when I would do that, like suddenly you could hear a pin drop in the room, and I would be a little dramatic about it.

But, you know, I would take my deep breaths. You know, but then they were all watching, and I was just like, “Okay, now I would like . . .” you know, “Can somebody tell me why I was starting to get angry? Why did my amygdala start to think that I was in danger?” And somebody would say, “Oh, because, you know, we were talking.” And I was like, “Yeah. And why did that make me mad?” “Well, because we weren’t listening to each other. We weren’t listening to you.”

And so then it was like a learning experience, not a punishment experience. I felt better. They felt better. And I was modeling, as an adult, modeling a different way of dealing with my emotions. And, you know, that’s not what I grew up seeing, and that’s not what they’re seeing most of the time.

Because, I mean, I didn’t learn about brain science until I was in my 40s, you know. Like, I mean, I really could have used this information a lot earlier. And when I wrote a book about the brain science called “Rosie’s Brain,” and I’ve heard so many adults say like, “Oh, my God, I read this to my kids and I couldn’t believe that I didn’t know anything about how my brain works.” And I’ve heard, like, psychologists say that they use it with their adult patients because it’s just an easy way to explain this concept that people really need to understand about themselves, and it’s happening to everybody.

Kevin: So let me ask you this. This is one last question. This is what I really want to know. And by the way, I think, Linda, you’re doing terrific work.

Linda: Thank you.

Kevin: This whole area is coming more into fruition and becoming more commonplace, but it is still viewed as one of those out there practices in a lot of our traditional schools. We’re fortunate on this show, this podcast that we have superintendents, school leaders, parents, teachers all over the country that regularly listen. So I want you to talk to a mid-size school district leader in a rural school district and who may be listening and may be intrigued by this, but as you mentioned earlier, with all the priorities and with the budget shortfalls and thus, and teachers wanting more pay and all these challenges, they’re not sure how they can incorporate this. And as is often the case, when they hear about a good idea that they like, but they don’t know how to execute on it, it goes nowhere.

Linda: Yeah.

Kevin: What I really want to know is what suggestions would you offer that superintendent in that small rural community that may feel like you’re onto something, this makes sense, or that principal in an urban school district that has all these other priorities and challenges? What advice would you give them on how to begin the process of at least exploring whether they can incorporate this in their school?

Linda: I mean, they should definitely call us up. We would love to talk to them. If people are interested, we usually suggest that they start with like a pilot and get teachers who are interested to sort of opt in to try out the curriculum, because we really find that it’s a very easy to use curriculum. It’s a very inexpensive curriculum. We’ve really, really tried to keep it as low cost as possible because we don’t want there to be any, you know, obstacles to kids having this kind of learning.

But if teachers are interested in trying it out, the results are so much better. And then they can show their colleagues like, “Look what’s happening in my classroom.” I mean, we hear this time and time again, like one teacher tried the curriculum and then everybody was like, “Oh, what’s happening in her classroom?” And then it spreads. I mean, that was my experience. That’s what happened teaching at Lafayette, and we just hear this all the time.

I don’t recommend that you say, “My school system is going to start using Peace of Mind now” and give everybody the book and say, “Go for it.” People need support. You know, we know that happens to teachers all the time. You need support, you need training, you need time. And I mean, what I hear from teachers all the time is that when they teach these skills, when they spend a little time focusing on the kids’ social and emotional well-being, everything else gets easier. The behavior is better. Kids cannot learn when they don’t feel safe, and when they don’t feel seen, and when they don’t feel heard, and when they don’t feel like it matters. And so giving some priority to their humanity makes them feel open and available to learn.

I heard your interview with Hedy Chang about chronic absenteeism.

Kevin: Oh, yes.

Linda: I was just writing a piece about the truancy problem in D.C. And, you know, it’s such a complicated issue, and there’s so many factors. But I really think that kids need to feel like it matters if they go to school. Like, that they’re valued just as human beings and not by what they can produce or achieve, but just that they matter just because they are who they are. And in my classroom, what I heard all the time was, you know, they’d say, “Ms. Ryden, this is the only place at school where I feel like I can be myself and where I can just relax for a minute.” And the kids are under so much pressure, they need us to value them just as human beings and see them. And teachers need that also.

Kevin: Yeah, well said. Linda Ryden, thank you so much for what you’re doing, and thank you for joining us on “What I Want to Know.”

Linda: Thank you so much for having me. I’m so grateful for this opportunity, and it’s so fun to talk to you.

Kevin: Thanks for listening to “What I Want to Know.” Be sure to follow and subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app so you can explore other episodes and dive into our discussions on the future of education. And write a review of the show. I also encourage you to join the conversation and let me know what you want to know using #WIWTK on social media. That’s #WIWTK.

For more information on Stride and online education, visit stridelearning.com. I’m your host, Kevin P. Chavous. Thank you for joining, “What I Want to Know.”

About the Show

Education is undergoing a dramatic shift, creating an opportunity to transform how we serve learners of all ages. Kevin P. Chavous turns to innovators across education, workforce development, and more to ask: “How can we do better?”

Related Podcasts

Listen to more podcasts about this topic.

Featured Resources

Discover more resources that address the topics impacting students, families, and educators today.